Tim Walz's campaign for Minnesota governor aims to bridge the great divide

Tim Walz was an enlisted soldier in the Minnesota National Guard in 1999 and defensive coordinator of the Mankato West High School football team. A student at the school, where Walz taught geography, wanted to start a gay-straight alliance.

This was three years after the president, a Democrat, signed a law forbidding same-sex marriage. Soldiers suspected of being gay in Walz's own unit could be discharged from the military. But Walz, now Minnesota's Democratic candidate for governor, had seen the bullying some students endured and agreed to be the group's faculty adviser.

"It really needed to be the football coach, who was the soldier and was straight and was married," Walz said. In other words, he would be a symbol that disparate worlds could coexist peacefully.

A southern Minnesota congressman, Walz, 54, has won six elections in a mostly rural, conservative-leaning area. The theme of his campaign — "One Minnesota" — reflects a politician who firmly believes he can straddle entrenched political divisions. Growing up in a small Nebraska town, steeped in the Catholic social justice traditions of his parents and expectations of service to country, Walz said he saw firsthand how government can help families.

"I never went to the Democrats. They came to me," Walz said, mentioning the GI Bill that funded college educations for him and his father, and the Social Security survivor benefits his mother lived on when his dad died young.

"There's a collective good," Walz said. "We all benefit from programs like that."

Walz is a college graduate who passed up the officer corps for enlisted life. He revels in a Norman Rockwell family life, beaming as he watched his daughter play soccer at Mankato West's "Senior Night" in September. But in an interview, he talked about his own "white privilege," echoing a term young progressives use to discuss race relations. He's a veteran who stands ramrod straight and hand over heart during the national anthem, and a man whose political career was born after he was blocked from entering a political rally for former President George W. Bush.

Walz, facing Republican Jeff Johnson for governor, said his experience crossing cultural and political fault lines positions him to rise above the partisanship that has stunted progress at the State Capitol. He hopes to forge unlikely coalitions to boost spending on schools, improve the health care system and accelerate repairs to the state's aging transportation system.

While Walz sells himself as a uniter, critics see an opportunist.

"Walz has campaigned for years in southern Minnesota as a moderate, but during this campaign for governor, he has abandoned any hint of moderation," said Gina Countryman, executive director of Minnesota Action Network, a Republican fundraising group trying to stop Walz. "He's run to the left on spending promises, tax increases, environment, mining and immigration issues, and Minnesotans are left to wonder where he stands on anything. If you ask him, he's apt to ask where you're from before answering you."

As a congressman, Walz has been hard to categorize. He voted for the Affordable Care Act and a failed cap-and-trade system that aimed to reduce emissions, but against bailing out the nation's banks and auto companies that many Democrats supported. He voted for tighter vetting of refugees into the U.S., then as candidate for governor said he regretted it. He once earned an "A" rating from the National Rifle Association and its endorsement as recently as 2012, but now denounces the group.

"In my core values of equity, and in freedom, those remain the same. But a rigidness in all situations? That's weak leadership," Walz said. He added: "If you can't change your mind you're never going to change anything."

Change and disruption are a theme in the life of Timothy James Walz, born in 1964 in West Point, Neb., to a stay-at-home mom and a school administrator. In the summers between school years, they farmed.

Driving in rural southwestern Minnesota recently, Walz spotted two turkeys bounding on the side of the road. "Big ones," he said, recalling how he and friends would bring their guns to school so they could hunt after football practice.

At 17, Walz joined the National Guard. "The path seemed like it was supposed to be kind of set," he said.

Then, when Walz was 19, his father died. Feeling life had been "ripped up," Walz meandered from Nebraska to Houston to Jonesboro, Ark., where he worked in a factory building tanning beds. He returned to Nebraska and earned a teaching degree at Chadron State College.

His father's death and the years that followed led him to live life with some risk, Walz said. Soon after graduating college, he was bound for China. It was just his second trip on an airplane, following his journey at 17 to Fort Benning, Ga., for basic training.

Through a Harvard program, Walz taught high school for a year, one of the first government sanctioned educators in the country. It was 1989, the year of the Tiananmen Square massacre. He still speaks a little Mandarin.

Back home and working full-time for the Nebraska National Guard, Walz was also teaching and coaching about an hour away from the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. There he met Gwen Whipple, a fellow teacher and a Minnesota native. On their first date (to the only movie theater in town, then Hardee's), she refused a kiss. He said they'd be married someday. Their honeymoon was a trip to China with 60 kids in tow.

After fertility treatments at the Mayo Clinic, the Walzes had a daughter, Hope, in 2001. Gus arrived in 2006, three weeks before Walz was elected to Congress.

In the fall of 1995, Tim Walz, then 31, was pulled over for going 96 miles per hour in a 55 mph zone. He said he'd been watching college football with pals. Walz failed a sobriety test and a breath test and later pleaded guilty to reckless driving.

"You have obligations to people," Gwen Walz said she told her husband. "You can't make dumb choices."

It was a gut-check moment, Walz said, an impetus to change his risk-taking ways. He no longer drinks alcohol; today his beverage of choice is a seemingly bottomless can of Diet Mountain Dew. At times, it seems to fuel Walz's dizzying conversational style, as he moves from education policy to football, words tumbling out like coins from a slot machine.

The Walzes ended up in Minnesota after Gwen Walz, who grew up in the Lincoln County town of Ivanhoe, decided she wanted to move home. They both got jobs at Mankato West and found a house within walking distance.

Settled into a life of teaching and coaching, Walz led the football team's defense, culminating in a state championship. And he was helping gay and lesbian students deal with bullying.

"There was no mandate to do this," said Jacob Reitan, a Mankato West student at the time who is now a Minneapolis attorney. "It was one teacher saying I know kids are suffering in the silent closet of fear and misunderstanding. What an important moment that was for me."

Walz retired from the National Guard after 24 years; in 2003 he served with his Guard battalion in Italy in support of U.S. forces in Afghanistan.

Three years later, the second President Bush was running for re-election, and Walz tried to bring a group of students to a Bush rally in Mankato. The goal, he said, was to show them politics up close. But one student was carrying promotional materials for Democratic challenger John Kerry, and the group was barred.

"It just seemed so wrong that there would be a gatekeeper, especially stopping young people from seeing the president in their hometown," Walz said. He signed up to volunteer for Kerry.

The 2006 midterm election saw Democrats elected in huge numbers nationwide, driven in part by the unpopularity of the war in Iraq. Initially viewed as a long shot, first-time candidate Walz went on to unseat Gil Gutknecht, a 12-year Republican incumbent.

The highest-ranking enlisted military member in the history of Congress, Walz took up veterans' issues when he got to Washington. Former Rep. Chet Edwards, a Democrat from a similarly conservative-leaning Texas district, said Walz paid attention to overlooked problems of military life, such as day care on military bases, mental health and suicide among soldiers and veterans, and pain management.

"He didn't take credit. His name wasn't out front," Edwards said. "But as one member of Congress, I can attest to his impact."

Walz held the seat through five more elections, including two in which Republicans made big congressional gains around the country, especially in rural districts. In 2016, Walz was narrowly re-elected even as President Donald Trump won his district by more than 15 points.

In 2011, Walz invited Julie Rosen, a longtime Republican state senator from southern Minnesota, to be his guest at the State of the Union. "I hope the amiability, respect, and dedication that Congressman Walz and I share will continue in the future," she said in a news release at the time.

Many Republicans saw Rosen as well-positioned to challenge Walz and win, but she never ran against him. Rosen now said she suspects Walz wanted to give her an up-close look at the difficulties of life in Washington.

"Pull!" Walz growled at a recent stop to shoot sporting clays at Caribou Gun Club and Hunting Preserve in Le Sueur, as he aimed his Beretta A400 12-gauge skyward. Commended for marksmanship in his military years, Walz used to visit the club twice a month.

The raw state and national debate over guns is one Walz said he's well-positioned to mediate. He said he can unite "responsible" gun owners with gun control activists behind legislation like red flag laws — letting law enforcement take guns from someone determined mentally unstable by a judge.

His shift angered many gun activists in Minnesota. Bryan Strawser, chairman of the Minnesota Gun Owners Caucus, said his group is impatient with elected officials who retreat from gun rights, and that Walz would pay dearly at the ballot box.

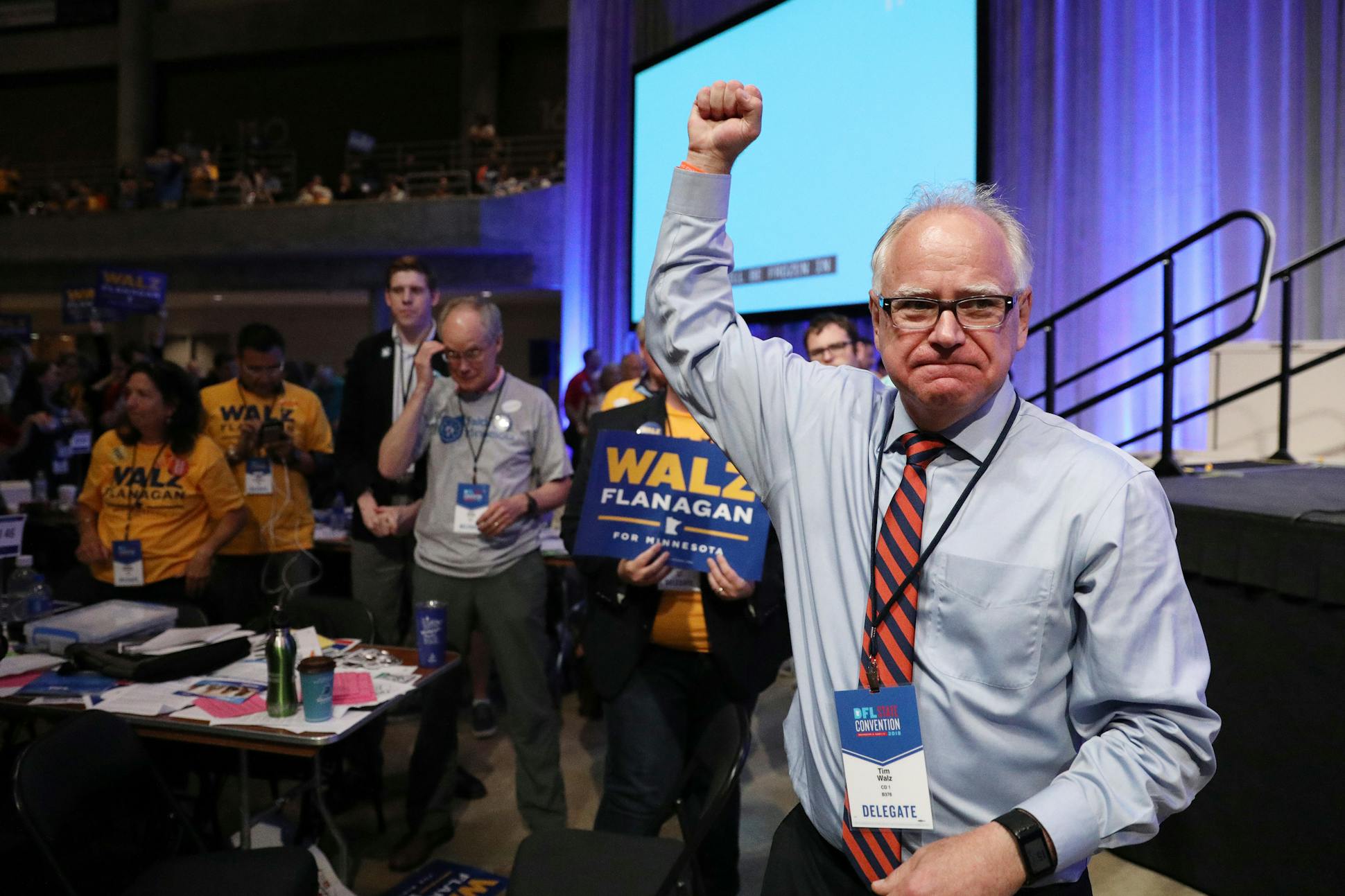

Despite losing the party endorsement at the DFL convention, Walz won the DFL primary. He has continued to court Democratic constituencies. Always capable of a fiery stemwinder, at a recent carpenters' union meeting he castigated Johnson's support for a right-to-work law.

"With us, that bill won't come to our desk. But if it does, we'll tear it up!" Walz said to thunderous applause.

At a recent debate, Johnson ticked off his case against Walz.

"I believe Minnesotans and Minnesota businesses are overtaxed, and Tim Walz believes we are undertaxed," Johnson said. "I believe that you should have more control over your health care. And Tim has said we need to move to a single-payer system. I believe we should cooperate with the federal government when it comes to illegal immigration enforcement. Tim believes we should become a sanctuary state."

Walz said he thinks the state can afford a more active government but would consider raising taxes on upper incomes. He's said he'd sign a gas tax increase to pay for transportation improvements. He defends sanctuary policies by arguing that state and local law enforcement should focus on state and local issues, not immigration. And he said "Medicare for All" — as Democrats call their plan to expand government health insurance — is a federal, not a state priority. But he does agree with it.

Joseph Eustice, a fellow command sergeant major who lives in Ortonville, served under Walz in the Guard. He said he's been voting mostly Republican these past few years but has faith in Walz.

"I don't always agree with Tim. I've disagreed with him about politics and other things," Eustice said. "But if you get a chance to talk to him, you'll have an exchange of ideas, and at the end, he'll either convince you, or he'll understand your viewpoint. And I think then he'll make a decision that he thinks is in the interest of everyone."